Common Go Footguns: Appending to slices #2

This post is a followup to Common Go Footguns: Appending to slices, where I demonstrated that appending to a slice can be a surprising source of impactful performance problems. While this post focuses on Go specifics, much of the methodology and thought process involved in this post applies to most performance related work.

We know that pre-allocating our slices is good. But, what if you don’t know how many items you need to append to your slice? What if you’re appending during an expensive O(n³) algorithm? Most engineers I’ve worked with would really resist doing O(n³) work just to know the size of a slice to pre-allocate. It seems quite wasteful. In the past I’ve conceded here.

That’s wrong. It’s worth it.

The Algorithm

For this post, I’m using the simplest O(n³) slice append algorithm I could think of.

| |

I theorize that counting the number of elements that are going to be added to the slice first by adding another O(n³) stage is actually faster than the original. Emphasis theorize. Yes, yes, I know, I’ve already given the game away with earlier bold claims. But when anyone makes an assertion about optimizations or performance it’s important to demand hard evidence. Acceptable kinds of evidence include benchmarks, metrics, and profiles. Claims without at least one of these types of evidence should be questioned. Until hard data is in hand, you have theories and nothing else. We’re going to focus on benchmarks for this post since this is only a demonstration.

The theorized improvement:

| |

Methodology

I ran the below benchmarks independently, starting each with an input slice size of 10, adding a 0 after every run until the benchmarks failed to finish. You may notice that the pre-allocation version goes for an additional order of magnitude.

| |

The Data

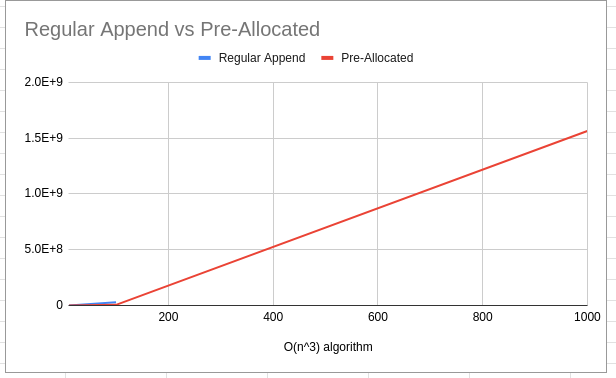

| Input Size | Regular Append (nanoseconds) | Pre-Allocated (nanoseconds) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 14863 | 9247 |

| 100 | 29635723 | 5594893 |

| 1000 | SIGKILL | 1563432682 |

Regular append with input of 1k couldn’t even finish, and received a SIGKILL. The Pre-Allocated version timed out after 60s on my machine with input of 10k.

The Pre-Allocated version doing an extra O(n³) pass is the clear winner here, being able to handle a full order of magnitude larger input than the original algorithm.

But, Why?!?

Big-O Is King (for this benchmark)

Our Data Structures and Algorithms courses should have taught us that O(n³) + O(n³) = O(n³). Spending the time to count the number of elements you’ll need to append doesn’t hurt you as n grows.

The cost of reallocating the underlying array does hurt. It hurts a lot.

While it’s true that append amortizes to O(1), the size of the data is O(n³). Every time the slice capacity needs increasing, we allocate O(n³) memory, and copy O(n³) data.

Memory Pressure

With pre-allocation we allocate O(n³) memory, no more. Without pre-allocation we have to allocate O(n³) memory many times. Every time the slice capacity needs to be increased we need a new larger array. On smaller hosts with large input data we risk the dreaded OOM killer. On larger hosts, all of this allocation means we bring the garbage collector into play.

Allocated memory does not get released to the system immediately. The Go garbage collector is a great thing, but it’s not magic. Anyone who’s spent time in the special hell of tuning the Java GC for a specific high performance workload will attest to how much garbage collection can wreck performance.

If I were to take a profile here, I’d wager we’d see that the allocations and garbage collection are why the appendON3 function’s benchmark gets SIGKILL at only a 1k input slice size.

Should we always pre-allocate our slices?

There are cases where pre-allocation might not be worth it. One example where the pre-allocation technique would not work is streaming data. It’s hard to pre-allocate a slice if you have no idea how much data is coming.

Conclusion

We have to understand that Big-O means 2 × O(n³) is still O(n³). Sometimes it’s easy to forget that fact. We also need to remember that memory allocation is not free, and the cost can rear its head in unexpected places.

For years, I had accepted the “We don’t know how big this slice is, and it’s expensive to count” reasoning. It wasn’t until I actually thought through the Big-O and memory implications that I realized something expensive like O(n³) is not a valid reason to avoid pre-allocation. The products I’ve worked on and reviewed would have benefited from a more rigorous thought process as well as sticking to good engineering practice of measure measure measure.

That doesn’t mean pre-allocation will always make sense 100% of the time. It means:

- Be thoughtful.

- Remember Data Structures and Algorithms courses.

- Measure.